I Campaigned For The 1967 Abortion Act, But The Job Was Only Half Done

In 1961 Diane Munday was in her late 20s. Married with three kids under the age of four, she got pregnant. Instantly she was certain – with every fibre of her being – that she couldn’t have another child, physically, psychologically or financially.

Photographed by Poppy Thorpe.

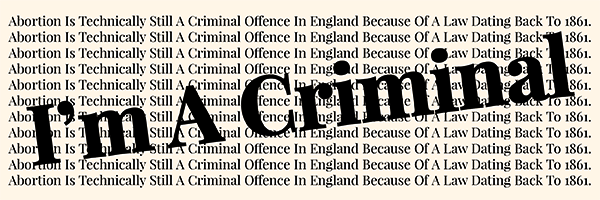

She wanted an abortion but the procedure was illegal. It’s hard to fathom that, with the so-called sexual revolution in full swing, the availability of the contraceptive pill for the first time and the advent of free love, Britain’s abortion legislation at the time consisted of a Victorian law – the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act – but it did.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

That piece of legislation made it a criminal offence for women to procure terminations and for medical professionals to perform them. Anyone who did so – including Diane – could be jailed for life.

That didn’t mean abortions didn’t happen, though. It just meant they weren’t safe. Backstreet abortions were a feature of everyday life and, as Diane reflects now from her mid-century modern living room in the same semi-detached home she inhabited at the time of her abortion, "hospitals would keep beds open after payday for women suffering complications from botched procedures".

Some abortions were allowed, in very limited circumstances to save a woman’s life or preserve her health. This was because of the Bourne judgement of 1938, which allowed for a pregnancy to be ended if it made "the woman a physical or mental wreck". However, these often came at a high price.

“

As I was coming around from the anaesthetic, all I could think about was a family friend – a dressmaker – she didn’t have a chequebook to wave around in Harley Street so she went to a backstreet abortionist. She died.

”

Diane was fortunate in many ways. She was able to pay a decent doctor and "buy" a legal abortion, as she puts it. It wasn’t cheap. She says she was quoted £150 initially but managed to negotiate it down to "around £90 plus a psychiatrist’s fee" which came in at approximately a tenth of her husband’s annual salary at the time. Fortunately, there were no complications, though if either Diane or her doctor had been found out they could have been prosecuted and imprisoned. However, an acquaintance had not been so lucky.

"As I was coming around from the anaesthetic, all I could think about was a family friend – she had been a dressmaker," Diane says, sitting on an Ercol chair in her living room, sipping coffee. "She had been in a similar situation to me, but she didn’t have a chequebook to wave around in Harley Street so she went to a backstreet abortionist."

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

She looks solemn for a moment and then says, starkly: "She died because my husband earned more than hers."

In the decade that led up to the 1967 Act, abortion actually became the leading cause of maternal deaths. There were between 50 and 60 women dying each year as the result of an unsafe abortion. Diane notes: "I’ll never forget speaking to the doctors at St Bart’s hospital in east London, where I was working as a researcher. They kept beds open every week, after payday, because they knew how many women would be admitted because of serious complications like septic bleeding from backstreet abortions."

A photograph of Diane sitting in her home office while working on the campaign for abortion rights in the 1960s.

Diane talking about abortion law reform on ITV in the 1960s.

It was after her own abortion, convinced that Britain’s restrictive laws were creating "one world for women with money and another for women without" that Diane began campaigning with the Abortion Law Reform Association. "I bought my health, my safety, I bought a mother for my children, I bought a wife for my husband," she says.

At the time, there was also a sharp focus on the fallout of the thalidomide disaster. In 1962, it was revealed that thousands of children had been affected by severe and even fatal foetal abnormalities after their mothers were prescribed the drug for morning sickness and sleeplessness. Because of the strict abortion laws in place, even women who knew their unborn baby might have been affected by the drug could not ask for the pregnancy to be terminated.

“

We didn't grow up hearing about abortions, you know, it was all very hush-hush. Even talking about it at all was radical.

”

"I’ll never forget the first time I stood up and said I had had an abortion at a Reform Association meeting," Diane says, smiling. "There was a gasp from a lot of people in the room. We didn’t grow up hearing about abortions, you know, it was all very hush-hush. Even talking about it at all was radical."

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

Today, women still use their stories as catalysts to bring about change. We’ve seen it on a global scale with the #MeToo movement online. What Diane and the other women did as part of the abortion reform movement was no different – they told stories, raised awareness, tried to change opinions and do away with stigma. They humanised an issue that those who were against abortion had done everything they could do to dehumanise.

"After I told my story, a lot of people came up to me and told me that they hadn’t actually heard anyone speak like that about an abortion before," Diane reflects. This decision to tell her story at a time when nobody spoke openly about abortion was radical. She was one of only a handful of women to do so.

"One by one, as I gave more talks, women from all walks of life would come up to me and say that they, too, had had an abortion. I realised then what a powerful weapon telling your story was – it made it clear that abortion was not about some nebulous woman in some nebulous place. It was me, them, here and now."

The Abortion Law Reform Association then sent a questionnaire to prospective MPs. One – a Liberal Democrat named David Steel – ticked the box which asked whether they would consider introducing a bill to reform abortion law if they were elected.

Steel was elected in 1965 and his private member’s bill was selected in the House of Commons. That bill passed after an all-night sitting on 27th October 1967, becoming what we now know as the Abortion Act.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

Diane was there, in Westminster. "We stayed up all night," she says, "just to keep things going." But when it did pass she was in no mood for celebrating.

"It sounds awful, but I was disappointed," she reflects, coming to life and sitting bolt upright in her chair.

“

After the 1967 Act was passed, champagne was poured and I said, 'I only want half a glass because the job is only half done'.

”

"We sat on parliament’s terrace, which looks out onto the Thames, and I couldn’t help but feel there was more to be done. Champagne was poured and I said, 'I only want half a glass because the job is only half done'."

This, she adds, is because she knew that the Act wouldn’t apply to Northern Ireland. "We were leaving those women behind," she says. "I also knew that it didn’t go anywhere near as far as it should in England and Wales (the law works slightly differently in Scotland) so it was always my hope to be able to complete the job."

In order to get the Act over the line, concessions had been made. Two doctors were required to sign off on an abortion, they were only allowed to be carried out in certain places and, crucially, the 1861 Act was not repealed but legislated over. This meant that despite the legalisation of abortion, it was still technically a criminal offence.

Trying to interview Diane about her campaigning is not always easy. She is impatient for change and, perhaps, tired of journalists asking her the same questions on a loop while nothing changes.

"We compromised," Diane says bitterly when I press her on her feelings about the ‘67 Act. "I always objected to the idea that doctors should sign off on a woman’s behalf – it is our decision what we do with our bodies. I’ve said ever since that it is my life’s work to see abortion decriminalised and made a medical as opposed to a criminal matter once and for all."

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

Over the years, Diane has received abuse. Red paint was splattered across her car, to symbolise the blood of the children she had supposedly murdered through her successful campaigning. She has a thick skin but is barely able to conceal the fact that the anti-abortion lobby in Britain still riles her.

She says she won’t rest until the 1861 Act no longer has any bearing on abortion law in Britain.

"We need decriminalisation for theoretical and practical reasons," she says. "The arguments for it are exactly the same as they were in the 1960s. Without it, women in 2020 will still be governed by an act of 1861. The world was different then, women’s place in the world was different. The world has changed but abortion law has not."

More than 50 years after the 1967 Abortion Act passed in the House of Commons, Diane Munday is still here, still talking and still telling the same story over and over again because she knows that’s how to bring about real change.

Please sign our petition and help us change the law to fix abortion provision once and for all.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT