We Need To Talk About The ‘Crazy Lesbian’ Trope

Photo by Fox Searchlight/Kobal/Shutterstock

The 'crazy lesbian' trope has long permeated popular culture. Whether a character is obsessive to the point of delusion (as in Black Swan or Mulholland Drive), driven to the edge by their unrequited love (as in Rebecca or All About Eve) or even murderous (as in Basic Instinct, Bound and Lizzie), their queerness is a defining factor in what 'drives them mad'.

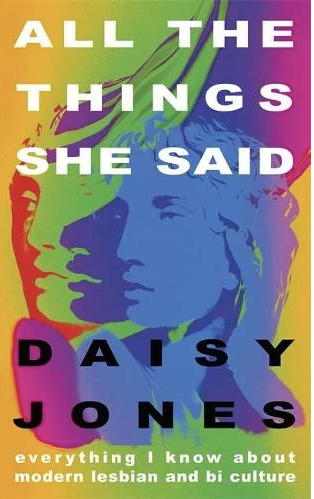

It's a building block in the cultural understanding of queerness – one that journalist Daisy Jones explores in her new book, All The Things She Said: Everything I Know About Modern Lesbian And Bi Culture. While it primarily centres on queer desire or relationships, it doesn't always. Daisy points to how queer presentation is often the threat in itself: the butchness of Matilda's unmarried (aka coded lesbian) Miss Trunchbull in contrast to Miss Honey is a prime example. "Sometimes these characters seem like warnings: this is what you'll be like if you choose a life outside of heterosexuality," she tell me. Like the depraved homosexual, the psychotic bisexual or the murderous trans person, it is a trope that has inadvertently defined how we think about mental health among queer people.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

The trope is an exaggeration: a caricature of a depraved, unstable woman driven to anger, hysteria or even violence by a desire that the world deems incompatible. It should be clear that this is not how people behave outside of scripts or novels. And yet it persists, set in opposition to the stark reality that queer women are statistically far more likely than the general population to reckon with mental illness: a report published by Stonewall in 2018 found that over half (55%) of LGBT women had experienced depression in the last year, for example. The crazy lesbian isn’t real and yet the crazy lesbian is real, leaving queer women stuck in the middle, often without the tools they need to reckon with their mental health.

The ‘crazy queer woman’ (as it doesn’t exist solely for lesbians) trope evolved from a heady mix of censorship, bigotry and fear. It’s not an invention of the age of cinema – it can be found in Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 vampire novel Carmilla and in Djuna Barnes’ 1936 novel Nightwood – but it was really distilled by the Hays Code era of Hollywood, which required that 'deviant' characters must not be rewarded or in any way sympathetic. This often meant that they’d be killed off or visibly punished, whether through literal punishment or the torture of their own mental anguish. Although the Hays Code was abolished in 1968, the tropes it produced linger on in the media we consume.

The reason why this trope persists is, in part, down to the double-pronged bigotry which queer women face time and time again: homophobia laced with misogyny. Women’s desire and agency is a direct threat to the patriarchal status quo and when that desire excludes men entirely, the threat is heightened. The queer woman has to be 'othered' by the narrative and the neatest way to do so is to make them obviously unhinged and therefore devoid of any charm for the male gaze.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

Even more than in media, the concept lingers in the minds of queer women. We internalise it, even if it’s to make fun of ourselves. When I ask Daisy about the ways it affects our self-perception, she says that she definitely absorbed it. "I can only speak for myself, but for a long time I definitely internalised the idea of ‘dyke drama’ being a thing, or this idea that women together are overly emotional, which is quite misogynistic when you scrutinise where that trope comes from and why." Despite recognising that the trope is not the lived experience of being a lesbian, it is still an easy catch-all for taking the piss out of yourself. "I still find myself rolling my eyes at myself and thinking, What a lesbian! if I'm giving a really dramatic and emotional speech or something," she adds. "As long as it's me taking the piss out of myself, then I think that's okay."

While we use the trope to make jokes at our own expense – especially if we are being overdramatic – it's unavoidable that it cements this idea that to be a queer woman in a world that vilifies you means you are inevitably driven mad. At first glance that seems true: the UK is experiencing an ongoing mental health crisis and LGBTQ+ people are suffering at significantly higher rates. According to Stonewall’s 2018 health report, 79% of non-binary people, 72% of bisexual women and 60% of lesbians said they had experienced anxiety in the past year. Seventy percent of non-binary people and 55% of LGBTQ women said they had experienced depression in the past year. Twenty-four percent of non-binary people and 13% of LGBTQ women had experienced an eating disorder in the past year. Across the board, these statistics also tend to be higher if you’re Black, Asian or minority ethnic, differently abled or from a socioeconomically deprived background.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

But it is too simplistic to say that X causes Y. To be a lesbian doesn’t inherently mean madness. But it does mean you live in a world where both your sexuality and mental ill health are stigmatised and therefore feed into each other.

The queer mental health crisis doesn’t arise from obsession or rejection or queerness in itself but from systemic failure. As Daisy puts it to me: "It's important to underline the fact that poor mental health among queer people is on average higher than that of straight people for a variety of reasons, all of which are societal and external and nothing to do with us." These external forces range from a greater likelihood of experiencing hate crimes and the mental repercussions of that, experiencing familial rejection to the point of homelessness and navigating microaggressions to slowly unpicking the ingrained shame about being queer.

As Daisy emphasises to me, "there is nothing distressing about queerness in and of itself, and actually queerness often feels like a real blessing" – but the impact of these external forces is worsened by a lack of accessible mental health support, specifically queer-friendly support, and a lack of range in depictions of queer women.

If we are to reconcile the unrealistic (though often entertaining) 'crazy lesbian' trope with the reality of the mental health crisis, we need radically overhauled mental health support in the UK and more queer women on screen who aren’t obsessive to the point of murderous. These are not problems that can be rectified overnight with a few more therapy slots available through the NHS or a couple of queer characters whose queerness is incidental to the plot (although both are helpful). As Daisy puts it, the queer mental health crisis and how we understand ourselves through culture is just a starting point.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

"Mental health services in the UK are completely underfunded, in general, and LGBTQ organisations and charities can't be a plaster for that wound. You can't have a fully trained team who specialise in intersectional needs if there isn't enough money being pumped into where we really need it. But also, mental health services are just the tip of a very huge societal iceberg. As I say in the book, mental health issues among queer and trans people will not magically disappear until queerphobia, biphobia, transphobia etc. disappear too, which will take more than a bit of funding and training. The dismantling, the representation, the attitude-shifting, will require mammoth work from the ground upwards."

As for the tropes that have inadvertently defined us for so long, making room for queer women not to be defined solely by their queerness or by their mental health helps alleviate the stigma that forces those two facets to be intertwined, while allowing the more compelling iterations to stick around.

"I feel reluctant to say, 'No more crazy queers in pop culture, please!' because some of my favourite pieces of pop culture have a psycho dyke element," says Daisy. "But I think what we can 'do' is continue to push for a wider range of lesbian and bi characters. They don't all have to fit into the same three tropes. I feel like it's okay to have psycho dykes on TV, so long as that's not all we have."

All The Things She Said: Everything I Know About Modern Lesbian and Bi Culture by Daisy Jones is out now on Hodder & Stoughton

This piece has been amended to attribute quotes to the author, Daisy Jones

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT