Recipes shared in home kitchens and passed between generations inform the way we eat just as much as the recipes we follow online. To celebrate this, we're interviewing the chefs, home cooks and food writers we love, where we'll be talking about how the food we make intermingles with ideas of tradition and cultural heritage.

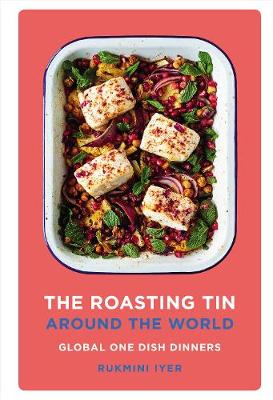

This week, we speak with Rukmini Iyer, the food writer behind the bestselling Roasting Tin series.

The way I like to think about cooking is that it should be as easy as possible in the method, but give back as much as possible in terms of flavour. The question I ask myself is, "What can I condense from the flavours you get from hours of prep?" and "How can I emulate a restaurant dish that's got loads and loads of components made by 16 different chefs?"

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

The goal is to make it really easy: you get a massive punch of flavour but you, as the cook, are really chilled out. That was the idea behind my Roasting Tin books and is the way I like to cook generally: how can I inject a massive quantity of flavour, or just finish it off with a bit of texture, or a really nice punchy acidic dressing... Elevating it so you're not just having a tray of roast veg or a bowl of risotto.

Cooking this way probably stems from growing up in an Indian vegetarian household where you don't just have rice and one curry, you have rice and three or four different curries. They're all fairly quick and easy to prepare, but you get that contrast of flavour with every bite – something a little bit sweet, something a little bit sour, something salty, and then you have rice (or in some Indian cultures you would have bread instead, like paratha or roti, but we're a rice-eating house). The idea is that you have a variety of flavours and textures just on one plate. So when I'm making something that is one pot or one tin, in the back of my mind I’m thinking that if I'm going to eat a whole plate of this, I want that interest there.

My earliest memories of cooking are with my mum: either doing something like stirring bechamel sauce standing up at the stove, or browning onions for curry. You've got to get your onions really lovely and caramelised and brown for most different curries as a base and that's something you just cannot do by going away – you have to stir it! So as soon as I was old enough, Mum would say, "Right, you want to help? Stand on the chair, stir the onions." My memories are of both Western and Indian styles of cooking.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

When you're in the kitchen cooking together, you don't just interact with the person there. With my mum we'll start making something and I'll ask, "Oh, how did Grandma make it?" and have a little chat about her. It's a way to remember the generation who aren't there anymore. There aren't many other contexts in which you can bring up people who aren't around anymore in a joyful, happy way, you know? It's a lovely, almost commemorative way of thinking about generations past through the way that they cooked. It's like the memories of the people who are absent are as present.

I think the recipe that I go to the most is very representative of my mum. It's pilau rice and you might think you can get it on any sort of takeaway menu but the way she makes it is just so good. You fry whole spices in butter: you've got cinnamon sticks, cardamom, cloves and bay leaf, and then you add in a big handful of cashew nuts (that was one of my jobs as a kid, halving the cashew nuts). And then you fry them in the butter which smells incredible. In Mum's version you then put freshly cooked rice in at that point so that the nuts stay really crisp and you fry off your rice in butter, before adding some more dry spices like ground ginger, ground cumin, ground coriander and salt.

It's just magic the way she makes it. I’ll make that in my own flat if I just want some comfort eating, or there's so many variations that I make now. I might cut out a lot of the spices and use Sichuan peppercorns. Or I might use saffron and almonds instead of cashews. I've done another version with pine nuts before. I've done it with olive oil as well when I've run out of butter – you could even do it with sesame oil if you're going to have an egg fried rice with whole black peppercorns. I love that she's given me a template and that it's always comforting in whatever guise I make it.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

I think that when you are actually benefiting from someone else's culture in your food writing, you should nod to wherever your sources are. Research and see if you can find some authentic voices and try and make sure you’re not seeing a cuisine through just one lens. You're trying to look at things through the point of view of people whose culture it is as well. Obviously there's nothing wrong with writing about other food cultures but I wouldn't want anyone to come to my Around The World book, for example, and think I’m the definitive voice behind how to make a Thai curry.

In my book I hope I’m quite open about the fact that this is my version of this dish that you can do in the oven quite quickly as a weeknight meal. And I've got a bibliography in the back to show that if you were interested in these food cultures, go do some further reading!

I think starting a dialogue about the fact that no one's really has the last word in food is so important. A recipe is the end point of so much more.

Rukmini was in conversation with Sadhbh O’Sullivan

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT