Why Wasn’t I Warned How Much My Brain Would Change During Pregnancy?

Photographed by Eylul Aslan.

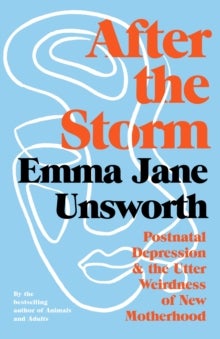

Emma Jane Unsworth is an award-winning novelist and screenwriter whose novel Animals is now a major motion picture. In her first nonfiction work, After The Storm, Emma takes a humour-filled but unflinching look at how the birth of her first child in late 2016 led to her developing postnatal depression, and what she learned as she pulled herself out of it. The realities of how carrying and caring for a child can impact your mental health are still massively underreported and misunderstood as shame, fear and dismissal keep new parents from speaking out or realising what they don't know.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

To mark UK Maternal Mental Health Awareness Week, we're publishing the following extract from After The Storm. It chronicles the ways in which pregnancy can literally change the brain and explores why we know in such intimate detail how the body changes but why, when you're pregnant, you're rarely told what happens in your head.

In May 2020, ten weeks into my fifth pregnancy (I want to acknowledge the three that didn’t work out, in addition to the first one that stuck around and resulted in my son’s birth), a kind and brilliant midwife called Didi told me at my booking appointment, eyes smiling above her corona mask, that I should be careful about reducing my antidepressants during pregnancy because at twenty-six weeks women experience a surge of cortisol, which helps get the baby’s lungs ready for the outside world, including the possibility of a premature birth. The effect of that cortisol surge on the woman is heightened anxiety.

I had never, ever heard about this before. But it feels pretty significant. I remember during the pregnancy with my son feeling very stressed around that time, and taking it out on Ian and, often, wayward cyclists on the cycle path outside my house who refused to stop at the pedestrian crossing. I may have yelled at a few. How many other things like this, how many hormone surges and brain spurts, might it help women to know about and prepare for? When people talk about the 'baby blues' it’s vague, and sounds trivial – pretty, almost. A colour you might paint the nursery. But there are huge changes occurring within women’s brains during pregnancy and early motherhood – changes we know astonishingly little about. The pregnancy ‘week-by-week’ diagrams show women’s bodies from the neck down. We are literally decapitated into unthinking vessels. In fact, women’s brains change more drastically and quickly during pregnancy and early motherhood than during any other period of their lives – including puberty.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

Scientists can’t yet say how maternal brain changes interact with things like sleep deprivation or trauma, which many women experience during childbirth. Or poverty, or abuse, which many women experience alongside motherhood. Importantly, they can’t yet say whether postpartum mood disorders are the result of something gone awry in typical changes to a mother’s brain, or whether they are caused by a triggering of other brain circuitry.

One in five women will have some form of mental illness during pregnancy or the postpartum period, according to a 2017 study by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. But even when it doesn’t tip over into illness, the brain changes are vast. In an article for the Boston Globe in 2018, Chelsea Conaboy reports that the flood of hormones women experience during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding (should they choose to do it) ‘primes the brain for dramatic change in regions thought to make up the “maternal circuit”. Affected brain regions include those that enable a mother to multitask to meet baby’s needs, help her to empathise with her infant’s pain and emotions, and regulate how she responds to positive stimuli (such as baby’s coo) or to perceived threats.’

Could this help to explain the heightened anxiety many new mothers feel? The forgetfulness of some things and the hypervigilance when it comes to others? The unmooring from our sense of identity?

Dr Jodi Pawluski is a Canadian neuroscientist and therapist who has extensively studied what she calls the ‘neglected neuroscience’ of the maternal brain, working largely with mice. (Turns out there are ethics when it comes to experimenting on human mothers, who knew?) I ask her what she thinks about the decapitated diagrams. ‘YES!’ she says. ‘Where are all the heads?’ She goes on to tell me that there is an overall decrease in grey-matter volume during pregnancy and the postpartum period – but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. She urges me to think of it as more of a ‘fine tuning’ instead. And while there is a decrease in neurogenesis (the making of new brain cells), which has been associated with forgetfulness, it’s maybe not so much about lack of new neurons than the existing neurons functioning more efficiently. Simply put: parts of the brain become more precise in function. These parts have been called ‘the maternal circuit’. ‘With modern imaging we have seen certain parts of women’s brains activated when babies cry, or when they see pictures of babies,’ she says. ‘The maternal circuit is different brain areas that are usually parts of other circuits but that come together and work together to mediate parental behaviours and proper parental responses.’

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

The work of Elseline Hoekzema at Leiden university in 2017 and 2019 shows that the decrease in volume of these brain regions is not associated with memory changes (at least not the memory types they looked at) but, in fact, with feelings of maternal attachment. So a lower volume of these brain areas correlate with greater feelings of attachment. As Dr Pawluski puts it: ‘Less is more when it comes to the brain and maternal care-giving.’

“

If I'd known there were massive brain changes afoot – if I'd known that unfamiliar emotions are part of a healthy experience of new motherhood – it might not have felt as much like my fault, or my failing when they tipped over into something else.

”

It is thought that the grey matter returns after a couple of years. I felt this was true to my experience, and found the science so reassuring. Wouldn’t it be great if there was a week-by-week diagram of pregnant women’s brain changes alongside the diagrams of their bodies and the baby’s development, so that we might know what to expect? So we could see which weeks we might feel a certain way, as well as discovering all the details about how big our bump will be, or which week the baby gets eyelashes, or starts drinking its own pee? If I’d known there were massive brain changes afoot – if I’d known that unfamiliar emotions are part of a healthy experience of new motherhood – it might not have felt as much like my fault, or my failing when they tipped over into something else. If we cut through the golden mythology and romanticism and show how the changes women experience are biological, not constitutional, then we might find that postnatal mental illness has, one day, more targeted diagnosis and treatment. Even considering a range of feelings for a typical pre- and postpartum experience is radical right now. It’s not all lovely-lovely-huggy-huggy – a lot of it is just weird, new and hard. Maybe if I’d known this, I wouldn’t have been so blindsided by it all.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

‘There’s a normal range of brain changes and feelings – and it’s not all happy,’ says Dr Pawluski. ‘When it persists and you can’t function then this is not healthy. But there is a normal range of emotions that need to be talked about and that are healthy to have.’

I tell a friend excitedly about these findings. ‘But would you have wanted to know?’ she asks. To which I answer a resounding ‘Yes!’ Everyone is different, but I want to be realistically informed. The idea that women can’t handle the truth of their experiences is a dangerous and pervasive one.

There is a huge reluctance to allow any negative thinking about motherhood. I was irked by the PR-sheeny bullshit that painted, from the start, a perfect depiction of motherhood and nicey-niceness that made me personally feel utterly unprepared for childbirth and the aftermath. I’m all for positive thinking. But, you know, laced with a good dose of reality. It’s not gloomy to recognise that a huge thing can comprise bad as well as good, is it? But where babies are involved it’s like we’ve got to slap on a rictus grin and chant, Everything’s lovely! Which is dangerous on so many levels. I made a cocaine joke at pregnancy yoga (that went down like a lead balloon, let me tell you). I won’t even tell you about going on a weaning course when I was hungover. All I will say is: purée and poo are not what you want to ponder at those times. Just call me the queen of baby-group faux pas.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

Why are there so many taboos? Why does pregnancy have to be perfect or bust? The mandatory twelve weeks of silence at the start of a pregnancy seems so damaging, for example. I know that this period of silence isolated me in the false shame of my first miscarriage. Silencing women through their reproductive experience seems to prevent so much useful information about the realities of fertility getting out.

For society, for the patriarchy, and crucially the capitalism that is symbiotic with it, it is useful to preserve the façade that motherhood is blissful. It keeps women doing it. It keeps them buying stuff to do it ‘right’. It keeps them buying things to quell the anxiety. And, ultimately, it keeps them feeling inadequate and inferior. During that pregnancy I was certainly busy beavering away at my little shopfront. I bought all the right things: the best cot, the fashionable buggy, even a weird vaginal exercise balloon to stop me tearing, the ‘Epi-no’ – as in: ‘Say NO to that episiotomy!’ (For the blissfully ignorant, an episiotomy is when they cut you open at your vagina so that you don’t split along your entire perineum.)

But in the back, in the storeroom of my anxieties, my true feelings were brewing. And I might as well have stuck that blue balloon somewhere else for all the good it did.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT