I’ve always been a rule-follower. It wasn’t just that I was a good girl who wanted to please people in authority positions — I was raised by two teachers. Not doing what was asked literally never even occurred to me. I made it through high school and college, and swam competitively, without straying from an assignment or task, and was 22 before I found out that my refusal to disobey was kind of awkward (at, gasp, a co-ed sleepover — where I quarantined myself to the couch out of respect). All this time I would’ve revered doctors as “in charge,” too. But when I found something weird in my breast, and suddenly didn’t feel like I was being respected or listened to, it hit me: Something had to change.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

I found the lump myself, lying in bed on a Sunday night while playing with my boobs, as one does when they have the kind of full and wonderful breasts they once dreamed of as a flat-chested pre-pubescent. But that night, my left one contained an undeniable lump. It felt huge, hard, and it hurt when I moved it. Being 24, I called my friends immediately. Also being 24, they told me to quit being dramatic and go to sleep. Next, I called my mom. There’s a huge gap between what you briefly learn in health class in high school and suddenly knowing what to do when you find a lump. My mom said call the doctor.

I slept poorly like I had been for weeks, frequently waking up soaked in sweat, which left me feeling exhausted and “off” every morning. When my Ob/Gyn’s office was finally open, I frantically called to share my discovery, but they were less concerned. It didn’t qualify as “walk-in hours worthy,” the receptionist said, offering me an appointment in a few weeks.

Instead, I showed up unannounced and barged through the waiting room full of pregnant women, insisting to be seen. My doctor acknowledged the lump, educated me on dense tissue and cysts, which would both be more likely than that other thing I thought it would be, and told me to come back in a month if the lump was still there. She assured me I was “too young” to have breast cancer, but I demanded a more conclusive answer, and eventually left with a prescription for imaging.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

An ultrasound technician, two days later, was also able to quickly confirm that there was a lump, and added that this wasn’t your average fluid-filled cyst. Even with this information she was ready to send me home. I was “too young” to have a mammogram, she said, because I was “too young” to have breast cancer. But I was already topless next to the diagnostic machines, prescription in-hand. Why not try another test? I didn’t relent until she agreed to smash my breasts flat and take a look. And then, at last, vindication — but also the worst-case scenario. Her face scrunched up to deliver the news: I needed to see a breast surgeon immediately.

And then, poof, I had earned the attention other cancer patients had. Doctors stopped gaslighting me and started being incredibly, brutally honest. A surgeon took tissue samples from my breast and armpit, and said, “I’m going to be honest with you, this looks and feels a lot like breast cancer.” And she was right; it was breast cancer. Suddenly I went from being “too young” to possibly get the diagnosis I knew I needed, to having a medical team drawing up an intensive treatment plan. It was all a blur, with one thought rising to the surface: There is no place for a young adult in the world of cancer.

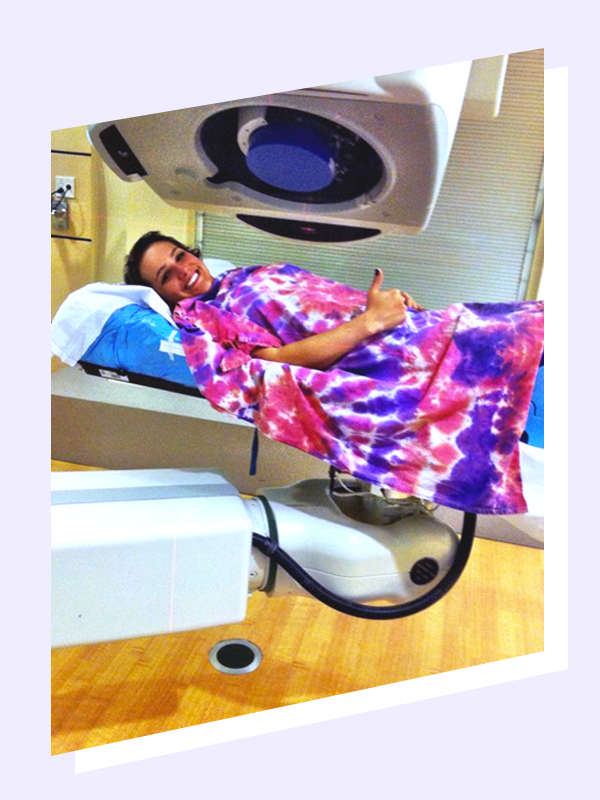

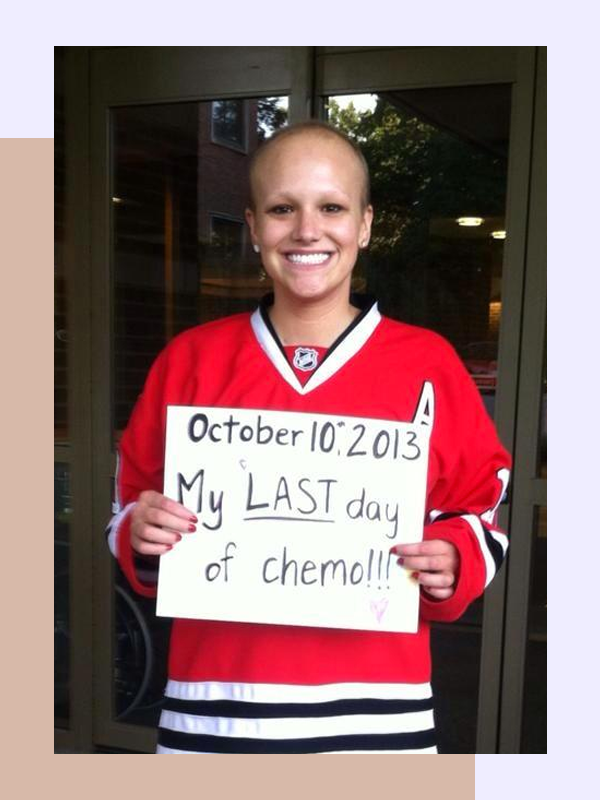

I endured six months of chemotherapy alongside members of the geriatric community, their wrinkled bodies attached to tubes and machines just the same as mine. I carried around a pill case that matched my grandfather’s, with a dozen different drugs for just as many symptoms. I met with doctors in offices decorated with balloon stickers and tiny handprints. My experience of being in limbo in the cancer ward was perfectly captured in a small “graduation” ceremony after I completed two months of radiation, standing alongside a 72-year-old and a 5-year-old.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

In support groups and on breast cancer retreats, I struggled to contribute to conversations with the other attendees on how cancer affects marriage or what it was like to parent through chemo. I never heard anyone else wonder how daily treatments would affect the career they literally just started, or how they managed dating and a social life while hairless and covered in scars.

I realized I would be alone with this, even when surrounded by people. My parents moved across the country to take care of me, but they were clearly terrified by the word “cancer,” and wondering how chemo, radiation and a double mastectomy plus reconstructive surgeries would affect me. My friends barely knew what a mastectomy was and couldn’t understand my prognosis. They wanted to show up for me, but also to make it fun.

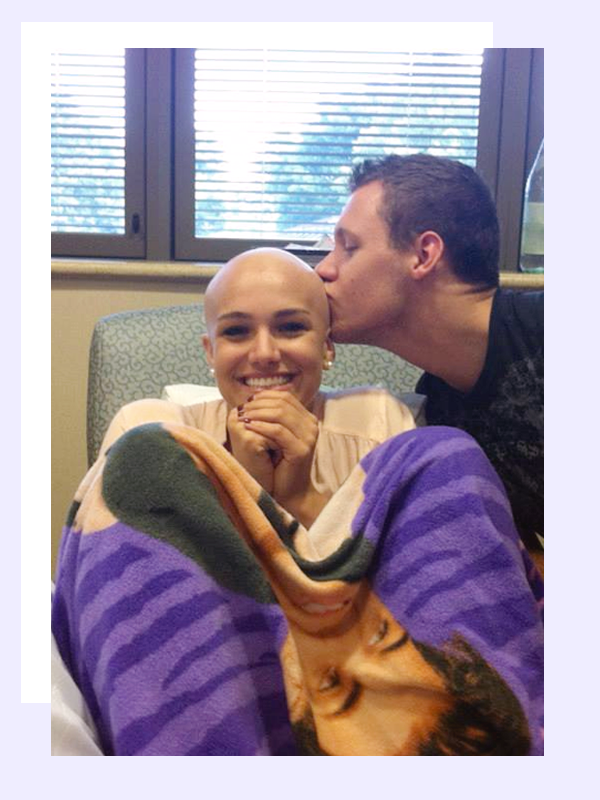

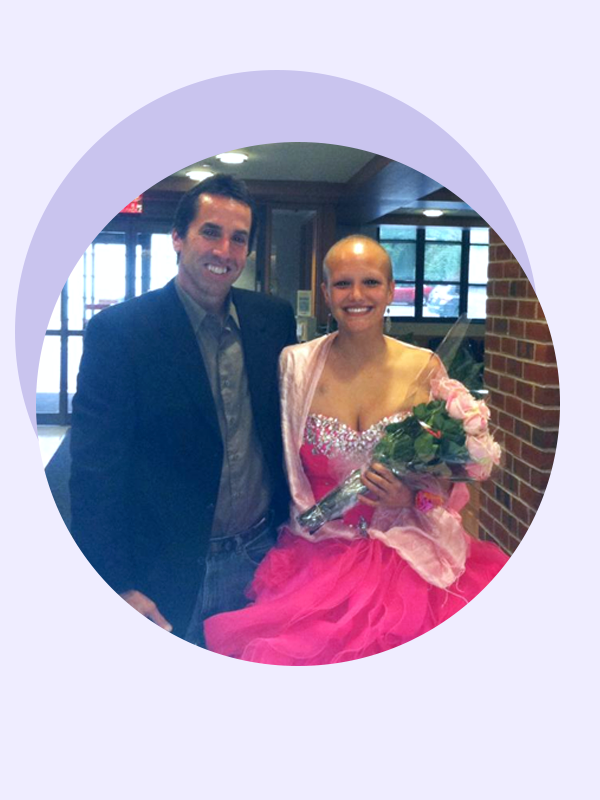

They brought me a Justin Beiber blanket for when the chemicals gave me chills. And when I came up with the idea to turn “chemo” into “themo,” they played along and appeared in large groups at my appointments dressed up in a theme (like Mustache Bash and Prom Night). It was an attempt to diffuse the obvious uncomfortable tension in the room (because CANCER), and to keep me hanging on. The choice was make it fun, find a way to rally, or I was quitting treatment. So they rallied. But come Friday night, my phone never rang.

Once, about a month into chemo and desperate to escape it, I went to a Sting concert alone. I sang and danced like a maniac for a few minutes until I felt too exhausted and sick, and laid in the back of my car sobbing until enough time had passed to go home letting my parents think I had a wonderful evening with friends. Being sick is a lonely endeavor — especially when the support is more often geared toward a community in which you don’t fit. But there was one very positive side effect to this: I learned that the power to support and fight for myself had always been within me. That, sick or not, I could do things for and by myself. And that no one knew better what I needed.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

And then came remission. My hair came back, in an awkward grow-out from fuzz to buzz cut to Justin Timberlake’s ramen noodle ‘do circa 1999. Scars spanned my nipple-less chest and my skin from radiation. My clothes were loose; I was chronically tired and I looked it. I thought this would be some Post-Cancer Celebration, but it was another frightening limbo, going from having every detail of my life planned around seeing the same receptionists and doctors day after day, to flying solo, again. My first day back to work I sat in my car for an hour before working up the courage to go in. I didn’t know who I was anymore.

For a while, in order to cope with having turned my body over to science and every conceivable doctor, I detached from it. While my friends were worrying about dating, I was seeing a fertility specialist to see if there were any freezable eggs left unscathed by chemo. I imagined horrified looks if I ever again let a man see me topless. Sex was canceled.

But then I found my power in the very same place. I was the one who had found the lump. I was the one who fought for the tests, the follow-ups, and the treatment I needed. I hadn’t been too young for cancer and I certainly wasn’t too young to advocate for myself in a world, in a field that sadly has far to go in how it prioritizes the health concerns of twentysomething women.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT

While I would never choose cancer, I wouldn’t change what happened to me. It forced me to cut the crap and grow up quickly. I was propelled into those gut-check moments when you find out who you really are. The girl who once wanted to please everyone else was replaced by a woman who understands what she wants and isn’t afraid to go after it. I learned the value of my voice and the importance of being an advocate for myself. In dark moments, I try to remember, I was taking myself seriously when everyone else thought I was “too young” to worry.

I’ve since found out that 70,000 young adults (ages 15 to 39) in the U.S. lose their youth to cancer every year. That is a huge group of individuals who are left to figure it out on their own, desperate to be heard and supported. I learned that cancer didn’t look like me, because the young adult cancer population didn’t have a face. So, I decided to become it.

Now, I work as an advocate. I get about a call a week either from a young adult with a new diagnosis or a friend of a friend who found something in their boob and doesn't know what to do about it. I sometimes struggle with not wanting to be defined by my disease, but it feels like there's a systemic failure in how women are educated about our bodies, and that's something that I personally can work to change. So, no: I wasn’t “too young” for cancer. I wasn’t too young to advocate for myself, and I'm not too young to be the teacher now, telling others that — sometimes, when it's important — it's okay to buck the rules.

October is National Breast Cancer Awareness Month. For more stories about detecting, treating, or living with breast cancer, click here.

AdvertisementADVERTISEMENT